The cast of Lost (2004-2010)

- goldenstateservicesj

- Sep 29, 2025

- 47 min read

SPOILERS!

Michael Emerson as Benjamin “Ben” Linus

“Hi, my name is Benjamin Linus and I’ve lived on this island all my life.”

While characters like John Locke with his profound philosophical depth, or the reluctant hero Jack Shephard are superior characters, Emerson’s portrayal of Ben stands as the pinnacle of acting in the series. Ben is far from a straightforward villain – he is a labyrinth of lies and ambitions and fleeting humanity that doesn’t fully come together in his very first appearances. This requires an actor to convey layers of deception without ever fully revealing the core of the character until the narrative demands it – which Emerson achieves stupendously well. Ben’s ability to manipulate extends beyond other characters (and himself), but also on audience’s perceptions, going from a victim to the puppet master to the pawn, often leaving you questioning his true intentions – of course this only works on the first watch, but even later, Emerson’s craft manages to make his deceptive layers almost endlessly intriguing and entertaining. From a minor guest role, Ben is expanded into what I believe to be the greatest performance of an antagonist on TV as Emerson, arguably better than anybody before or after him, humanizes a villain.

Jack: “And the other people on this plane. What’s gonna happen to them?“ Ben: “Who cares?”

Locke: “I thought you said you had no idea why he was trying to find the island.” Ben: “I wasn’t being entirely truthful.” Locke: “Yeah. When are you ever entirely truthful.”

Ben’s introduction in the second season nicely sets the little stage for Emerson’s masterful handling of the initial (but also the subsequent) mystery, immediately establishing him as a figure shrouded in enigma. As Henry Gale, a disoriented balloonist who crashed on the Island and whose wife supposedly died, Ben is captured by the survivors and subjected to a brutal series of interrogations in the Swan station’s armory. Emerson plays this initial phase with a disarming desperation, even fragility and consistent fear – however this is brilliantly and eerily textured by Ben’s subtly noticeable manipulation of the characters around him. Even more, there are subtle cracks in this facade, like a quick smirk or a too-calm response under torture by Sayid or an inappropriate moment of teasing, that create a sense of unease that slowly builds suspense around this meek character:

“Of course, if I was one of them – these people that you seem to think are your enemies – what would I do? Well, there’d be no balloon, so I’d draw a map to a real secluded place like a cave or some underbrush — good place for a trap – an ambush. And when your friends got there a bunch of my people would be waiting for them. Then they’d use them to trade for me. I guess it’s a good thing I’m not one of them, huh? You guys got any milk?“

Even if I had to judge Emerson’s performance solely from this short guest run, his score would still be very high as his control over the many possible outcomes of the character feels super-humanely complete and his skillful minimalism is able to ingeniously sustain suspense. As revelations unfold and Ben is confirmed as the leader of the Others, Emerson seamlessly transitions to the role, retroactively coloring earlier scenes even more vividly.

Locke: “You [Ben] are the man behind the curtain, the wizard of Oz.”

Alex: “That’s what my father does. He manipulates people.”

At the core of Ben’s character lie an insatiable ego and lust for power, manifesting in his tyrannical control over the Others and his supposed importance for the safety of the Island. Leader Ben rules with an iron fist, demanding unwavering loyalty while weaving webs of manipulation in the background to maintain his authority. Ben is a pathological liar, consistently fabricating realities to suit his needs – whether claiming to speak for Jacob or spreading misinformation about himself or using psychological ploys to get into the mind’s of individuals. Emerson is brilliant at capturing this manipulation through Ben’s precise, almost clinical delivery of falsehoods and of the truth – it is velvet and wit. Ben’s manipulation extends to psychological warfare, from feeding Locke’s faith to getting help from Jack. However, Emerson’s portrayal paints Ben as a despot whose clinical charisma masks a profound insecurity about his need for power, making his dominance not just oppressive, but intellectually riveting, as his perverse charisma magnetically draws viewers in despite his terrible actions.

Ben: “So, which one are you?” Locke: “I’m sorry?“ Ben: “Are you the genius or are you the guy who always feels like he’s living in the shadow of a genius?”

Roger Linus: “Listen…if it makes you feel any better, I will do my best to remember your birthday next year.” Ben: “I don’t think that’s going to happen, Dad.” Roger Linus: “What do you mean?” Ben: “You know, I’ve missed her too. Maybe as much as you have. But the difference is, for as long as I can remember, I’ve had to put up with you. And doing that required a tremendous amount of patience. Goodbye, dad.”

Ben’s goals of serving the Island and Jacob might be noble pursuits, but what truly cements Ben as a monster is his unwavering belief that the end justifies the means taken to an extreme through his obsession of maintaining his power, viewing the Island as a sacred entity demanding his absolute devotion. Ben’s devotion borders on fanaticism (though it could also be read as opportunism) and deems the Island worthy of any sacrifice, including genocide as evidenced by his orchestration of the Dharma Purge. Emerson embodies this monstrosity not through overt villainy, but through sociopathic detachment, as if Ben’s atrocities are mere administrative decisions – Emerson’s wide eyes are an especially powerful tool as they convey far more with their many differently charged stares than ten times more dialogue. Ben’s obsession isolates him, fueling a cycle of violence where losses are collateral in his quest for control, rendering him an irredeemable figure whose humanity is eroded by his own ideology (not necessarily by his actual morals and personality – though his inner machinations I leave to psychologists to analyze).

Sayid: “Juliet, you lived amongst the Others, why would Ben say the people coming here intend to do us harm?” Juliet: “Because he’s a liar. And he’s trying to scare us, that’s what Ben does.”

Ben: “You’ve been here 80 days, John. I’ve been here my entire life! So how is it that you think you know this island better than I do?” Locke: “Because you’re in the wheelchair, and I’m not.”

Ben’s envy and jealousy toward John Locke form his first pivotal undercurrent, driving much of his antagonism and revealing the cracks in his mostly self-assured facade. Locke, with his innate connection to the Island represents everything Ben craves, but evidently lacks: a pure and genuine faith and of course his “specialness” bestowed upon him by the Island itself, as Ben’s specialness is self-proclaimed and mostly unvalidated. Ben resents Locke’s effortless communion with the mystical forces he has spent decades serving and views him as an interloper threatening his status, especially when Locke hears Jacob’s voice (even if it wasn’t) in the cabin while Ben cannot. Emerson conveys this through quietly yet intensely charged interactions between the great characters, where Ben’s moments of sarcasm thinly veil seething bitterness. The rivalry first reaches its peak as Ben shoots Locke (Emerson simply brilliantly portrays Ben’s ego acting out, while also some very conflicting emotions he is unable to fully process in that scene):

“I was one of the people that was smart enough to make sure that I didn’t end up in that ditch. Which makes me considerably smarter than you, John.”

and it culminates in Ben strangling Locke off-Island in a hotel room – a desperate act to eliminate the rival who exposes Ben’s spiritual lacking which is self-manipulated into an act of helping the Island – underscoring Ben’s willingness to destroy what he envies most – even if he still admires the person:

“I’ll miss you, John. I really will.”

Locke: “Except for his [Ben] mouth moving, he’s harmless.”

Another of the many challenges Emerson faces and overcomes is how to make a nerdy man with a bookish appearance into a menacing and foreboding antagonist. Physically unassuming, with gentlemanly manners and a soft-spoken demeanor, Ben could easily be dismissed as harmless, yet Emerson infuses him with a quiet terror within his mindset that makes him more threatening than any brute on the show. It’s mostly in the eyes – the cold, calculating orbs, but the deliberate monotone of his voice can beautifully drip with implied threat and consistent eeriness. His confrontations with Widmore or Jack or Locke, showcase how Emerson uses stillness as a weapon (when he betrays the stillness the scene becomes even more brutal – as his many murders show), making Ben’s presence loom larger than it should have, externalizing his intellectual and sociopathic menace that lingers. It is an incredible subversion whose performative depth lies in the unpredictability and the psychological hold Ben exerts.

“’Why’? You’re [Juliet] asking me ‘why’? After everything I did to get you here, after everything I’ve done to keep you here, how can you possibly not understand… that you’re mine!“

Roger Linus: “I thought I was gonna be the greatest father ever. You know? I guess it didn’t work out that way.”

The death of Alex, Ben’s adopted daughter, serves as the catalyst for his staggering unraveling, unleashing a torrent of guilt that exposes the human fissures in his self-constructed sociopathic facade and marks a turning point in his arc. As the mercenaries sent by Widmore execute Alex before Ben’s eyes after he refuses to surrender, a direct consequence of his prioritization of the Island over her safety, bluffing that she means nothing to him in a failed negotiation,:

“She’s not my daughter. I stole her as a baby from an insane woman. She’s a pawn, nothing more. She means nothing to me. I’m not coming out of this house. So if you want to kill her, go ahead and do it…”

Emerson captures the raw catatonic shock in that moment through Ben’s shattering disbelief, his wide eyes reflecting a vulnerability rarely seen from the character to that point. As a grand manipulator, Ben has convinced even himself of his sociopathic detachment, believing his love for Alex pales against his loss of power over the Island, yet this event pierces that delusion, forcing him to confront the human cost of his bad choices and the humanity at his heart – initiating a veeeery slow erosion of his armored psyche.

Widmore: “And what makes you think you deserve to take what’s mine?” Ben: “Because I won’t be selfish. Because I’ll sacrifice anything to protect this Island.”

“I’m here, Charles, to tell you that I’m going to kill your daughter. Penelope, is it? And once she’s gone, once she’s dead, then you’ll understand how I feel, and you’ll wish you hadn’t changed the rules.”

Ben’s grieving process initially manifests as vengeful hatred and brutal anger toward those he blames (primarily Widmore) channeling sorrow into righteous retribution. He becomes driven by rage, planning to murder Widmore’s daughter in return – but this facade cracks as the series progresses, revealing an even more powerful sense of remorse. Through the final two seasons, Alex’s death becomes the base for Ben’s redemption which lies in the painful acknowledgment that his sacrifices through the years have hollowed him out, leading to the fact of his responsibility for her death. Emerson navigates this shift with beautiful nuance, allowing glimpses of vulnerability, from tears to painful expressions, to destroy Ben’s previous stoicism, transforming hate into a catalyst for self-reflection.

“Go home, Sayid. Once you let your grief become anger, it will never go away. I speak from experience.”

The Man in Black: “I think you’re lying.” Ben: “Lying about what?” The Man in Black: “That you want to be judged for leaving the Island and coming back because it’s against the rules. I don’t think you care about rules.” Ben: “Then what do I want to be judged for, John?” The Man in Black: “For killing your daughter.”

“When Charles Widmore’s men came, they gave me a choice. Either leave the Island or let my daughter die. All I had to do was walk out of the house and go with them. But I didn’t do it. So you were right. John, I did kill Alex. And now I have to answer for that. I appreciate you showing me the way, but I think I can take it from here.”

Dead is Dead stands as perhaps the most crucial episode for Ben’s evolution, where he finally confronts his culpability in Alex’s death and the depth of his paternal love head on, seeking judgment from the Smoke Monster. This surreal trial forces Ben to directly deal with his regrets, revealing a man tragically haunted by regret and an enormous capability for empathy (one could even argue him feeling too much is the source of his villainy, not feeling too little – emotions towards the “wrong” things that fuel his seemingly sociopathic behavior). Emerson’s performance here is revelatory as he makes the supernatural judgment tangible and delicately realizes the sympathy for the devil that humanizes Ben without excusing his monstrosities – it’s kind of incredible how the most powerful part of his judgment is actually the final disbelief at Monster’s conclusion: “It let me live.” The episode wonderfully underscores Ben’s internal war, blending confession with just a little bit of lingering defiance, marking a pivotal step toward the end of his progression.

“Sometimes good command decisions get compromised by bad emotional responses.”

Ben: “Why do you want me to kill Jacob, John?” The Man in Black: “Because, despite your loyal service to this Island, you got cancer. You had to watch your own daughter gunned down right in front of you. And your reward for those sacrifices? You were banished. And you did all this in the name of a man you’d never even met. So the question is, Ben, why the hell wouldn’t you want to kill Jacob?”

Sadly, the master manipulator finds himself manipulated by the Man in Black disguised as John Locke leading to Ben’s murder of Jacob in his final potent act of ego and misery that echoes his many past betrayals. Paralleling his patricide of his biological father to join the Others, Ben kills his surrogate father figure, Jacob, out of resentment and lack of love he had showed him, stabbing him in the heart after being convinced that Jacob’s indifference towards Ben justifies it:

Ben: “Oh… so now, after all this time, you’ve decided to stop ignoring me. Thirty-five years I lived on this island, and all I ever heard was your name over and over. Richard would bring me your instructions – all those slips of paper, all those lists – and I never questioned anything. I did as I was told. But when I dared to ask to see you myself, I was told, ‘You have to wait. You have to be patient’. But when he asked to see you? He gets marched straight up here as if he was Moses. So… why him? Hmm? What was it that was so wrong with me? What about me?!“ Jacob: “What about you?”

Despite sacrificing everything for the Island, Ben feels unappreciated, his devotion unrewarded. Emerson portrays this betrayal solely through the lens of despair – Ben’s stabbing of Jacob is a cathartic release laced with immediate horror at what he has done. The acknowledgement of the terrible consequences shows has far his transformation has come, yet the act still highlights his selfish core in his final horrible decision – but what will also lead to more self-reflection.

Lapidus: “You [Ben] make friends easy, don’t you?”

As Ben realizes the Man in Black’s deception, another wave of guilt engulfs him, propelling his shift toward heroism in the final season. First, he must reckon with the monstrosity at core of his personality, articulated in the eulogy at John Locke’s funeral:

“John Locke was a…a believer, he was a man of faith, he was… a much better man than I will ever be. And I’m very sorry I murdered him.”

The admission is delivered with a sincerity that Emerson realizes through Ben’s difficulty of processing his emotions and it strips away pretense and acknowledges Locke’s superiority. Secondly in his absolutely heartbreaking plea to Ilana that lays bare his soul:

Ben: “I watched my daughter, Alex, die in front of me. And it was my fault. I had a chance to save her, but I chose the island. Over her! All in the name of Jacob. I sacrificed everything for him. And he didn’t even care. Yeah, I stabbed him. I was so angry. Confused. I-I was terrified that I was about to lose the only thing that had ever mattered to me: my power! But the thing that really mattered…was already gone. I’m sorry that I killed Jacob. I am. And I do not expect you to forgive me, because…I can never forgive myself.” Ilana: “Then what do you want?” Ben: “Just let me leave!“ Ilana: “Where will you go?“ Ben: “To Locke.” Ilana: “Why?“ Ben: “Because he’s the only one that’ll have me!“

This raw confession, the most raw Ben will ever get, cements his path to redemption. Emerson fully externalizes the unimaginable amount of pain that has been simmering in Ben from Alex’s death forward – capturing both the paternal heartbreak and the terrifying thought of his culpability into a single powerful moment. Emerson is even able to masterfully realize the tragic farce at the core of his humanity in that final line that finally and fully lays bare himself to himself.

“So yes, I lied. That’s what I do.”

Eventually, Ben aids in saving the Island (and by extension the world) alongside the survivors in the climactic final confrontations, later assisting Hugo as the new protector to govern it more justly than Jacob, offering administrative knowledge drawn from his experience. However, Ben still grapples with unresolved issues, reflected in the flash-sideways purgatory where he is a history professor caring for his ailing father, Roger, in a reversal of their abusive dynamic, and, most poignantly, mentoring his star student, Alex, prioritizing her future over his ambitions and fostering her potential. The purgatory tasks him with making his worst decision again, but now he chooses correctly. When scheming to blackmail the principal for his job, Ben abandons the plan to protect Alex’s academic prospects, sacrificing his ambition for her. Emerson portrays Dr. Linus with gentle warmth, but same calculating stares underscore how his ambition is still there, but his monstrous ego hadn’t had the time or circumstance to fully develop.

Roger Linus: “That’s why I signed up for that damn Dharma Initiative, and took you to the island, and they were decent people. Smarter than I’ll ever be. Imagine how different our lives would’ve been If we’d stayed.” Dr. Linus: “Yes, we’d have both lived happily ever after.” Roger Linus: “No, I’m serious, Ben. Who knows what you would’ve become.”

Alex: “Why would someone want to hurt you? You’re, like, the nicest guy ever.” Dr. Linus: “Guess they had me confused with somebody else.”

After Desmond awakens his memories, Ben finally gets the chance to apologize to John Locke face to face, admitting his failings in a heartfelt exchange outside the Church. This humility-filled moment (and all the others in the purgatory) beautifully fulfills Ben’s lifelong search for human connection, bridging the envy that defined their rivalry and allowing Ben to sit outside the Church, reflecting on his unreadiness to move on until fully reconnecting with Alex also. Emerson profoundly delivers the confession, allowing Ben’s walls to crumble into something completely genuine, a fitting capstone to his arc of deception.

Ben: “I’m very sorry for what I did to you John. I was selfish, jealous. I wanted everything you had.” Locke: “What did I have?” Ben: “You were special, John… and I wasn’t.” Locke: “Well if it helps, Ben, I forgive you.” Ben: “Thank you, John…that does help. It matters more than I can say.” Locke: “What are you gonna do now?” Ben: “I have some things I still need to work out. I think I’ll stay here a while.”

Hurley: “I could sorta use someone with, like, experience. For a little while. So…will you help me, Ben?“ Ben: “I would be honored.”

Transforming Ben from a deceptive mass murderer into a figure of poignant self-awareness and reflection; from manipulative tyrant driven by ego and obsession to humbled advisor finding solace in human connections. Far beyond just sympathy for the devil and incredible entertainment value, Emerson fully realizes the agonizing reclamation of humanity of an absolute, genocidal monster who has always recognized its own darkness, but only decides to confront it when put to its utter and pitiful breaking point.

“I am not a bad person.”

The Best Acting Moment: explaining himself to Ilana S06E07

Verdict: 5

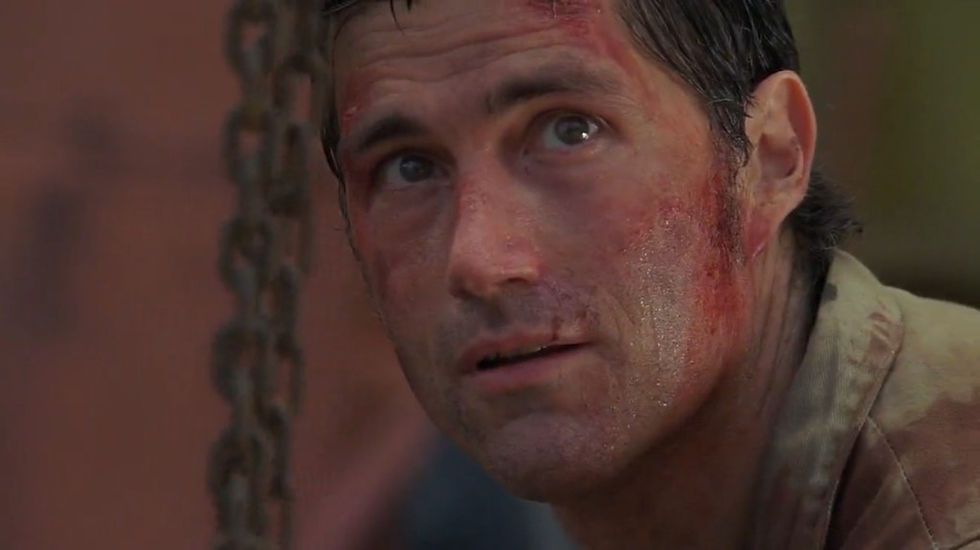

Terry O’Quinn as John Locke and the Man in Black

Nurse: “John, you fell eight stories and survived, OK. I don’t want to hear about what you can’t do.”

John Locke is simply put the greatest character that the writers of Lost have created, a figure whose journey of faith, destiny and redemption symbolically develops in profound and heartbreaking ways. O’Quinn is completely up to the task as he infuses the character with vulnerability, desperate determination and an almost constant sense of tragedy, making him one of the most powerful emotional cores of the series. However, in the final seasons, O’Quinn also demonstrates remarkable versatility in a complete 180 degree turn, embodying the wonderfully evil Man in Black who is disguised as John Locke. This transformation allows O’Quinn (and the writers) to explore diametrically opposed facets while inhabiting the same physical form. Even though I do not believe it to be the best in the show, O’Quinn’s performance is still one of the greatest in TV history.

“You don’t know who you’re dealing with! Don’t ever tell me what I can’t do, ever! This is destiny. This is destiny. This is my destiny. I’m supposed to do this, dammit! Don’t tell me what I can’t do!”

Locke: “Why do you find it so hard to believe?!“ Jack: “Why do you find it so easy?!“ Locke: “It’s never been easy!“

Locke is revealed early on as a mentally and physically broken individual, perpetually in search of something greater than himself to believe in, which fuels his anger and obsessiveness before, but also after arriving on the Island – even though he believes himself to be reborn there. Prior to the crash of Oceanic Flight 815, Locke was a paraplegic confined to a wheelchair, the result of a completely devastating betrayal by his own father, a conman named Anthony Cooper, who pushed him out a window and before that stole his kidney. The physical disability mirrors his deeper emotional scars – abandonment by his parents, failed relationships and a dead-end job. This is what eventually leaves him isolated and desperate for purpose – not, as he believes, the paralysis. His pre-Island life is marked by outbursts of rage and obsession – “don’t tell me what I can’t do!” at those who doubt him, a mantra that underscores his obsessive need to prove his worth. On the Island, this pattern sadly persists. The miraculous restoration of his ability to walk upon crashing amplifies his faith into the Island to the extreme, but it doesn’t heal his inner turmoil, leading to obsessive pursuits and often alienating others with his faithful intensity. O’Quinn captures this all-encompassing brokenness in staggering detail, making Locke’s search for meaning feel raw and human.

“I never even knew who my parents were. A couple of years ago, my birth mother found me, and… She told me, I was special! And through her, I met my real father. Great news, right? Well, he pretended to love me just long enough to steal my kidney because he needed a transplant! And then he dropped me back in the world like a piece of trash. Just like he did on the day that I was born! You want your damned 30 dollars back? I want my kidney back!!!“

Randy Nations: “What is it with you, Locke? Why do you torture yourself? I mean, imagining you’re some hunter? Walkabouts? Wake up, you can’t do any of that.”

“The struggle is nature’s way of strengthening it.”

Despite enduring a constant stream of tragic hardships, Locke maintains an unyielding faith in the Island’s purpose and destiny. His faith has been broken numerous times in his pre-Island existence and the Island consistently tests him with sacrifices and misinformation. Yet, Locke’s belief, at the end, persists, viewing these setbacks as necessary exams from a higher power rather than random cruelty. O’Quinn infuses these moments with conviction even when Locke’s mindset is momentarily broken – as Locke pounds on the Hatch in desperation only for a light to shoot into the sky as if answering his plea. This faith isn’t entirely blind optimism, but a hard-won armor against a lifetime of disappointment, making Locke uniquely and miraculously special for the story’s progression. O’Quinn also very cleverly embodies Locke’s faith as both inspiring and burdensome.

“But I’ve looked into the eye of this Island. And what I saw was beautiful.”

Emily Locke: “I want to tell you that you’re special. Very special. You are part of a design.“

“My name is John Locke, and I’m responsible for the well-being of this island.”

Central to Locke’s mindset is his conviction of being “special”, positioning him as an apostle who mistakenly believes himself to be the messiah, enlightened yet fundamentally as lost as everyone else. He interprets his paralysis cure as a sign of divine selection by his god (the Island), declaring himself reborn and destined to lead other to salvation, but this self-perception is laced with some delusion. In reality, Locke’s enlightenment doesn’t eradicate his pre-Island flaws – he remains angry, obsessive and self-centered, and there are individuals who are just as or even more special than him. O’Quinn masterfully conveys this irony as he emphasizes how Locke’s supposed rebirth is superficial and his actions are still driven by ego rather than true divine wisdom. This hubris blinds him to the Island’s true signals, turning his zeal and fanaticism into another tragic flaw.

“Boone made it fall. Then he died. A sacrifice that the Island demanded.”

“This island, it changed me. It made me whole.”

Locke discovers the faith he has always searched for on the Island, but he doesn’t find self-discovery – he evolves into a hero sometimes, into a fanatic at others and always into an unhealthily stubborn man, with his lifetime of tragedies finally granting him a purpose to persevere. From a lonely, embittered soul met with betrayal after betrayal and tragedy after tragedy, Locke finds solace in the Island’s miracles, channeling his pain into heroic acts like providing or defending the group. Yet, this faith manifests fanatically, as in his obsession with the Others or the Smoke Monster, nearly dooming everyone out of a stubborn belief, but also saving them on other occasions, like in his obsession with pushing the button in the Hatch.

Sun: “I don’t think I have ever seen you angry.” Locke: “I used to get angry. All the time. Frustrated too.” Sun: “You are not frustrated anymore?” Locke: “I’m not lost anymore.”

Jack: “I need for you to explain to me what the hell’s going on inside your head, John. I need to know why you believe that that thing wasn’t going to…“ Locke: “I believe that I was being tested.” Jack: “Tested?” Locke: “Yeah, tested. I think that’s why you and I don’t see eye-to-eye sometimes, Jack – because you’re a man of science.” Jack: “Yeah, and what does that make you?” Locke: “Me, well, I’m a man of faith. Do you really think all this is an accident – that we, a group of strangers survived, many of us with just superficial injuries? Do you think we crashed on this place by coincidence – especially, this place? We were brought here for a purpose, for a reason, all of us. Each one of us was brought here for a reason.” Jack: “Brought here? And who brought us here, John?” Locke: “The island. The island brought us here. This is no ordinary place, you’ve seen that, I know you have. But the island chose you, too, Jack. It’s destiny.”

“All that matters is they’ve got to come back. I have to make them come back. Even if it kills me.”

As Locke embarks on his off-Island mission to reunite the Oceanic Six and return them to the Island, only to face repeated rejection and deepening despair O’Quinn gets his best foundation for an externalization of Locke’s tragedy in the show. Adopting the alias Jeremy Bentham after turning the frozen wheel and being transported to Tunisia, Locke, with assistance from Widmore, travels the world to convince his former companions, Sayid, Walt, Hurley, Kate and Jack, to go back, each encounter met with dismissal or outright refusal that erodes his emotional resolve:

Sayid: “Why do you [Locke] really need to go back? Is it just because you have nowhere else to go.”

Kate: “You ever been in love, John?” Locke: “What?” Kate: “I think about you sometimes. I think about how desperate you were to stay on that Island. And then I realized… it was all because you didn’t love anybody.” Locke: “That’s not true. I loved someone… once. Her name was Helen.” Kate: “What happened?” Locke: “Well… it… it just didn’t work out.” Kate: “Why not, John?” Locke: “I was angry. I was… obsessed.” Kate: “And look how far you’ve come.”

Locke: “Jack, the people I left behind need our help. We’re supposed to go back.” Jack: “-because it’s our destiny? How many times are you gonna say that to me, John?” Locke: “How can you not see it? Of all the hospitals they could’ve brought me to, I end up here. You don’t think that’s fate?” Jack: “Your car accident was on the west side of Los Angeles. You being brought into my hospital isn’t fate, John. It’s probability.” Locke: “You don’t understand. It wasn’t an accident. Someone is trying to kill me.” Jack: “Why? Why would someone try to kill you?” Locke: “Because they don’t want me to succeed. They wanna stop me. They don’t want me to get back because I’m important.” Jack: “Have you ever stopped to think that these delusions that you’re special aren’t real? That maybe there’s nothing important about you at all? Maybe you are just a lonely old man that crashed on an Island. That’s it.”

O’Quinn captures this erosion masterfully, shifting from a determined prophet with a sense of profound purpose to a broken, isolated figure as his expressions convey the crushing weight of failure. The episode culminates in Locke’s attempted suicide which is interrupted by Ben, who manipulates him with false hope just before strangling him to death.

Ben: “You’re [Locke] so desperate to figure out what to do next, you’re even asking me for help. So here we are, just like old times. Except I’m locked in a different room, and you’re more lost than you ever were.”

“I was never meant to do anything! Every single second of my pathetic little life is as useless as that button! You think it’s important? You think it’s necessary? It’s nothing. It’s nothing. It’s meaningless. And who are you to tell me that it’s not?“

The gargantuan tragedy of John Locke lies in his unfulfilled quest for significance – a narrative thread powered exactly by the emotional depth of O’Quinn’s performance. Locke’s life is a cascade of heartbreaks: abandoned by his parents, manipulated by his father, losing his love, losing the ability to walk and ultimately strangled by Ben in a seedy motel. O’Quinn brings visceral emotion to each and every of these lows, his eyes conveying profound despair and flickering hope making Locke’s tribulations absolutely gut-wrenching. This tragedy resonates because Locke dies believing he has failed, one last time being bombarded with the most powerful question for a man of faith: “I don’t understand” – unaware of his pivotal role in the grand scheme, with O’Quinn’s nuanced acting amplifying the pathos to unforgettable levels. A tragic irony that underscores Locke’s lifelong journey as susceptibility to con artists seals his fate as a pawn and puzzle piece in the grander picture.

“There’s no helping me. I’m… I’m a failure.”

Eddie: “The psych profile said you [Locke] would be amenable for coercion.”

Locke’s strong faith becomes a weapon in the wrong hands, exploited due to his naivety and desperate desire for meaning, turning him into a pawn and a corrupted hero. Easily manipulated by figures like Ben or the Man in Black, who dangle promises of specialness. Locke’s pain and rage that destroyed his relationships off-Island, resurface to make enemies on the Island also. O’Quinn is so good exactly because he never looses his conviction, even if his confidence isn’t always there – beautifully maneuvering his relationship with the Island signs. His yearning is weaponized, corrupting his heroism into fanaticism. Ironically, we learn Locke was incredibly meaningful, guiding Jack Shephard, the true messiah of the Island god, toward faith and eventually to his sacrifice, a powerful revelation that reframes Locke’s heartbreaking tragedy as essential.

Charlie: “Trust him? No offense, mate, but if there was one person on this island that I would put my absolute faith in to save us all, it would be John Locke.”

“I realize how strange this all is – me, here. But I assure you, Sun, I’m the same man I’ve always been.”

After his tragic death, Locke’s journey is reversed through a false resurrection, revealing he was never the universe’s most important person, but a vessel for the Man in Black to impersonate him and manipulate other characters for his grand scheme. O’Quinn doesn’t immediately pivot to pure evil – instead, he embodies a version of Locke that’s uncharacteristically confident, using familiar parts of his personality to manipulate. This fake Locke retains Locke’s physicality, but infuses it with sly assurance which aids his deceptions until the full reveal.

Sawyer: “Who are you? ‘Cause you sure as hell ain’t John Locke.” The Man in Black: “What makes you say that?” Sawyer: “‘Cause Locke was scared. Even when he was pretendin’ he wasn’t. But you? You ain’t scared.”

Jack: “You’re not John Locke. You disrespect his memory by wearing his face, but you’re nothing like him.”

Once fully exposed as the Island’s monster, O’Quinn excels as an almost gleefully evil presence, yet one that is especially menacing and foreboding. He also masterfully unveils the ethos of this entity that has been trapped on the Island for centuries, desperate to escape and cynical to the consequences it might cause. The Man in Black is an embodiment of destruction, willing to extinguish the Island’s light, and the world, for a taste of freedom. O’Quinn’s performance is chilling, decorated with predatory smiles and suspenseful expressions conveying eons of resentment, making its motivations (freedom at any cost) understandable yet dreadful.

“What I am is trapped. And I’ve been trapped for so long that I don’t even remember what it feels like to be free.”

The Man in Black: “You can accept the job. Become the new Jacob. And protect the Island.” Sawyer: “Protect it from what?” The Man in Black: “From nothing, James. That’s the joke, there is nothing to protect it from, its just a damn Island. And it will be perfectly fine without Jacob or you, or any of the other people; whose lives he wasted.”

“Because… my mother was crazy. Long time ago, before I… looked like this… I had a mother, just like everyone. She was a very disturbed woman. And, as a result of that, I had some growing pains. Problems that I’m still trying to work my way through. Problems that could have been avoided had things been different.”

Ben: “If you can turn yourself into smoke whenever you want, why do you bother walking?” The Man in Black: “I like the feel of my feet on the ground. Reminds me that I was human.”

“My walkabout. An adventure in the outback. Man against nature. But they wouldn’t let me go. And I sat there yelling at them. Shouting at them that they couldn’t tell me what I can’t do. But they were right. I’m sick of imagining of what my life could be out of this chair, Helen. What it would be like to walk down the isle with you because its not gonna happen. So if you need me to see more doctors, have more consults, if you need me to get out of this chair, I don’t blame you. But I don’t want you to spend your life waiting for a miracle because there is no such thing.”

In the flash-sideways, Locke is broken only physically, his mental growth has occured on its own in this afterlife limbo, where he’s become a grounded man, almost a man of science, who doesn’t cling to or believe in miracles, accepting he may never walk again while finding his happiness with Helen. Unlike his obsessive Island self, this Locke is content with his “failings”, his relationship untampered by past fixations, embodying quiet human connection as more important than fervent faith. O’Quinn portrays this version with gentleness and humility, finding the meaningful contrast that only Locke alone can grow out of his anger and obsession, no Island needed.

Jack: “What happened, happened…and…you can let it go.” Locke: “What makes you think letting go is so easy?” Jack: “It’s not. In fact, I don’t really know how to do it myself. And, that’s why I was hoping that…maybe you could go first.”

Eventually, the flash-sideways Locke is persuaded into faith by Desmond’s interventions to awaken his memories, leading him to accept Jack’s surgical offer on the ground of his infamous man of faith mentality:

Locke: “But what if all this…maybe this is happening for a reason. Maybe you’re supposed to fix me.” Jack: “Mr. Locke, I want to fix you, but I think you’re mistaking coincidence for fate.” Locke: “You can call it whatever you want, but here I am. And I think I’m ready to get out of this chair.”

This eventually leads to his acceptance of who he really is (a man of faith) and waking up, but he also retains his mental growth from the sideways realm which beautifully facilitates his letting go. O’Quinn’s subtle shift from skepticism to wonder and happiness just wonderfully closes John Locke’s expansive arc.

Jack: “Why John Locke?” The Man in Black: “Because he was stupid enough to believe he had been brought here for a reason. Because he pursued that belief until it got him killed.”

O’Quinn’s emotionally powerful performance renders Locke’s story into a cautionary tale of blind faith’s perils. How unwavering belief, untempered by self-awareness, can lead to manipulation and ruin. Yet, through humanization in flashbacks, revelations of his true importance and corruption of the Man in Black, Locke emerges as an ultimately tragic, but also as an ultimately ironic character whose pathos will walk in this universe forever.

“My job is to convince people to push a button every 108 minutes without them knowing why or for what.”

The Best Acting Moment as John Locke: the death of Jeremy Bentham S05E07

The Best Acting Moment as the Man in Black: “why aren’t you afraid?” S06E12

Verdict: 5

Henry Ian Cusick as Desmond David Hume

Widmore: “This is a 60 year MacCutcheon, named after Anderson MacCutcheon, esteemed Admiral from the Royal Navy. He retired with more medals than any man before or since – moved to the highlands to see out his remaining years. Admiral MacCutcheon was a great man, Hume. This was his crowning achievement. This swallow is worth more than you could make in a month. To share it with you would be a waste, and a disgrace to the great man who made it – because you, Hume, will never be a great man.”

Portraying Desmond Hume presents a challenge for any actor, given the character’s abundance of intensely emotionally charged moments that risk veering into melodrama if not handled properly. Desmond’s arc is filled with high-stakes drama, heart-wrenching separations, supernatural visions, time-displacements and triumphant reunions, all of which demand a performer capable of grounding the fantastical in raw, believable humanity. Cusick rises to this task pretty masterfully, infusing Desmond with the kind of vulnerable intensity that ensures that his scenes of anguish resonate as authentic rather than overwrought, balancing Desmond’s romantic idealism with tormented realism, where the wrong decision would make the character cartoonish.

Penny: “Desmond, what are you running from?” Desmond: “I have to get my honor back… and that’s what I’m running to.”

Introduced at the start of the second season, Desmond quickly ascends to one of the show’s most intriguing characters, mostly because of Cusick. Initially encountered as the enigmatic inhabitant of the Swan station, frantically inputting the numbers 4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42 into a computer “to save the world”, Desmond exudes a mix of paranoia and charisma that hooks you instantly. Cusick brings a magnetic presence – his wide-eyed urgency and Scottish dialect infuse the role with stunning authenticity. As flashbacks reveal his romantic backstory, Desmond evolves from a quirky hermit into a more of a multifaceted figure, blending desperation and quiet strength in his love-fueled quest.

Desmond: “And what makes you think I would just run away?” Widmore: “Because you’re a coward.”

Charlie: “Because you [Desmond] turned some key, that makes you a hero? You’re no hero, brother. I don’t know how you’re doing it, but I know a coward when I see one!”

Desmond’s off-Island story frames his journey as a coward’s arduous struggle toward eventual heroism – a journey rooted in romantic and tragic past mistakes that culminates in his unlikely heroic salvation of the world from electromagnetic disaster in season two. Before the Island, Desmond is a flawed man: a former monk and later a soldier who is fired from both jobs, driven by self-doubt and a fateful encounter with Penelope Widmore, the love of his life and daughter of the antagonistic Charles Widmore. His cowardice manifests in failed romantic relationships and a disastrous attempt to win Penny’s father’s approval (which he seeks even more than her love – as supposed cure for his cowardice) by sailing around the world in a race sponsored by Widmore, only to crash on the Island. This tragic backdrop is marked by alcoholism and regret. Cusick captures Desmond’s slow evolution with poignant subtlety, his performance highlighting Desmond’s internal conflict as he transitions into the sacrificial hero. In the season two finale, Desmond turns the fail-safe key, imploding the station and absorbing a massive electromagnetic discharge to prevent global catastrophe – a redemption through bravery, delivered with raw intensity by Cusick.

Eloise: “You may not like your path, Desmond, but pushing that button is the only truly great thing that you’ll ever do.”

Hurley: “That guy sees the future, dude.”

Following the Swan station’s implosion, Cusick masterfully humanizes Desmond’s supernatural ability to glimpse into the future, particularly in the tragic buildup to the death of Charlie Pace. The electromagnetic exposure grants Desmond precognitive flashes that are centered on Charlie’s impending deaths forcing him into a Sisyphean cycle of intervention. Cusick very nicely portrays the haunting power of the weight of foreknowledge, turning abstract visions into tangible torment. In Flashes Before Your Eyes, Desmond’s consciousness hurtles back to his pre-Island life (in the moment of the Swan station implosion), attempting to alter his breakup with Penny, only to tragically learn the universe course-corrects itself. Cusick excels in this episode, blending confusion and determination as Desmond navigates temporal disorientation, making the mind travel feel visceral rather than a gimmick. When Desmond foresees Charlie’s sacrifice in the Looking Glass station, the tragedy of the scene lies in Charlie’s willing death, which Cusick only amplifies, humanizing his supernatural ability as a kind of curse of inevitable loss.

The Man in Black: “You’re out here in the jungle, alone, with me. No one else on earth knows you’re here. So I wanna know, why aren’t you afraid?” Desmond: “What’s the point in being afraid?”

“I won’t call for eight years. December 24, 2004. Christmas Eve. I promise. Please, Pen.“

However, Cusick is at his finest depicting Desmond’s mind traveling consciousness oscillating between 1996 and 2004 in The Constant, risking his death without a “constant” anchor. Cusick’s portrayal of escalating confusion and cathartic emotion makes the abstract concept of consciousness travel palpably harrowing, blending vulnerability with urgency as he seeks Penny’s phone number across time. The episode further exemplifies Desmond’s progression from a self-tormented victim to a resilient survivor. As Desmond’s mind fractures, Cusick layers panic with poignant sense of longing. The episode reaches its climax as Desmond calls Penny, which showcases Cusick’s mastery over Desmond’s romantic intensity – relief and surprise and love and tears converge in a cathartic payoff brimming with emotional authenticity that humanizes the surreal escapade of the episode.

Desmond: “I love you, Penny. I’ve always loved you. I’m so sorry. I love you.” Penny: “I love you too.” Desmond: “I don’t know where I am but,” Penny: “I’ll find you, Des,” Desmond: “I promise,” Penny: “no matter what-“ Desmond: “I’ll come back to you.” Penny: “I won’t give up.” Desmond: “I promise.“ Penny: “I promise.“ Both: “I love you.”

Charlie: “So, how did you manage to leave her behind and come here?” Desmond: “Because I’m a coward.”

As Desmond finally escapes the Island, his heroism is rewarded with a reunion with Penny and a peaceful life away from Widmore, raising their newborn son Charlie. Sadly, his unique abilities make him indispensable to the Island, leading to his kidnapping by Widmore under Jacob’s guidance. Back on the Island, Widmore exposes him to intense electromagnetism, briefly killing him and propelling his consciousness to the flash-sideways realm, inspiring in him a new purpose to awaken others in that realm, while giving him a new sense of his purpose on the Island. This exploitation peaks when the Man in Black manipulates Desmond into uncorking the Island’s heart, initiating apocalypse – here Cusick beautifully conveys Desmond’s tragic optimism, believing it will transport him to the alluring afterlife with Penny, only to realize his error in horror. Happily, Jack saves both Desmond and the Island by recorking the source and letting Desmond go from his duties to the Island:

Jack: “Desmond, you’ve done enough. You want to do something, go home and be with your wife and son.”

“I want him [Widmore] to respect me.”

In the flash-sideways, Desmond embodies a successful thug in Widmore’s corporate empire. He is admired by Widmore and prosperous, fulfilling what he once thought he desired the most from life. But he is devoid of family and love, highlighting what he truly needs. As Widmore’s trusted operative, he lacks the emotional anchors of his Island life, a stark contrast to his original self’s priorities. Cusick portrays this alternate Desmond with slick confidence – a man whose charm masks an inner emptiness, underscoring the hollowness of success without the human connection.

“I’m not looking for any companionship. I’m here to work.“

Desmond: “Well, I’ve got a great job, lots of money, get to travel the world. Why wouldn’t I be happy?” Charlie: “Have you ever been in love?” Desmond: “Thousands of times.” Charlie: “That’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about spectacular, consciousness-altering love. Do you know what that looks like?”

His Island experiences make him the first to awaken in the flash-sideways, reuniting him with Penny once more and transforming him into a new heroic figure who aids his friends in remembering their lives to collectively move on in the afterlife. After the electromagnetic blast from Widmore, Desmond’s consciousness bridges realms, prompting him to orchestrate awakenings, with Cusick infusing these acts with purposeful zeal, turning Desmond into a magnetic benevolent catalyst for closure.

Daniel: “You’re [Desmond] the only person who can help us, because, Desmond, the rules don’t apply to you. You’re special. You’re uniquely and miraculously special.”

In the end, Desmond Hume emerges as a modern Odysseus, enduring a perilous quest back to his Penelope, navigating tempests of time and fate to reclaim his love. Cusick’s impressive achievement lies in rendering this strange case of one man’s time-traveling mind not just believable, but deeply compelling, tangible and even inspiring, grounding sci-fi absurdity in the emotional truth of this man’s love.

“I’ll see you in another life, brotha.”

The Best Acting Moment: the phone call with Penny S04E05

Verdict: 5

Matthew Fox as Dr. Jack Shephard

Jack: “I don’t believe in destiny.” Locke: “Yes, you do. You just don’t know it yet.”

In the first two seasons it seemed to me that Fox was still finding his footing in embodying the character’s initial skepticism and leadership burdens, often delivering solid, but not amazing groundwork. However, as the real meat of Jack’s arc emerged in later seasons (the poignant transformation from a reluctant leader into a tragic hero through hardships and changing world-views), Fox rose surprisingly and magnificently to the challenge, delivering a remarkable depiction of one man’s path to self-discovery that not only redeems his personal flaws, but also saves the world.

“I’m not a hero.”

Jack: “How are they? The others.” Locke: “Thirsty. Hungry. Waiting to be rescued. And they need someone to tell them what to do.” Jack: “Me? I can’t.” Locke: “Why can’t you?” Jack: “Because I’m not a leader.” Locke: “And yet, they all treat you like one.”

Jack’s beginnings on the Island establish him as an absolute man of science, characterized by stubbornness and a compulsive need to “fix” everything around him, positioning him as a skeptic and control freak who relies on rationality to navigate the spiritual chaos of the Island. From the moment Oceanic Flight 815 crashes, Jack emerges as the de facto leader, using his skills as a spinal surgeon to tend to the wounded and organize the survivors, all while repressing his own fears to project strength. His mantra of quick thinking and rationalism at any cost drives him to reject any notion of the Island’s mystic properties, viewing them as coincidences and illusions that could only foster false hope. Fox captures this early rigidity through a very tense physicality and an unbridled intensity (in contrast to O’Quinn’s usual calm) as Jack controls and manages others, often at the expense of his own emotional well-being.

Achara: “You [Jack] are a leader. A great man. But this… this makes you lonely. And frightened. And angry.”

Christian Shephard: “Don’t choose, Jack, don’t decide. You don’t want to be a hero, you don’t try and save everyone because when you fail… you just don’t have what it takes.”

Jack’s deep-seated daddy issues and marital problems form the core of his need for human connection – two fractured relationships that haunt him and fuel his compulsive behavior. His father, Christian Shephard, a fellow surgeon, instilled in Jack a fear of failure by suppressing his need to be a hero – in many ways this leads to their paternal rift that leaves Jack grappling with unresolved guilt and inadequacy in the eyes of his father. Similarly, his marriage to Sarah, whom he miraculously fixed after a car accident by restoring her ability to walk, crumbles under his workaholic tendencies and jealousy. Fox portrays these vulnerabilities again with intensity as he in flashbacks reveals a man desperate for validation through fixing others, yet unable to mend his own broken parts.

Sawyer: “See, kids are like dogs: you knock ’em around enough, they’ll think they did something to deserve it. Anyway, there’s a pay phone in this bar. And this guy, Christian… tells me he wishes he had the stones to pick up the phone, call his kid, tell him he’s sorry, that he’s a better doctor than he’ll ever be he’s proud and he loves him. I had to take off, but something tells me he never got around to making that call. Small world, huh?”

Desmond: “Oh, and you [Jack] don’t believe in miracles?”

Jack’s confrontations with the Island’s resident man of faith, John Locke, highlight his absolute denial of the supernatural, creating ideological clashes that underscore his rational worldview. Locke, with his unwavering belief in the Island’s miracles serves as Jack’s antithesis, pushing him to question science’s limits through their many confrontations. Jack dismisses Locke’s mysticism as a dangerous delusion, leading to tense standoffs. Fox is quite good in these scenes, mostly because of his intense chemistry with O’Quinn – his performance conveys a simmering frustration and intellectual disdain that wonderfully bounces off Locke’s absolute conviction and an almost beautiful sense of belief.

Locke: “Lie to them, Jack. If you do it half as well as you lie to yourself, they’ll believe you.”

Ben: “Let me ask you something, Jack. Why do you wanna leave the Island? What is it that you so desperately want to get back to? You have no-one. Your father’s dead, your wife left you, moved on with another man. Can you just not wait to get back to the hospital? Get back to fixing things?”

This denial fuels Jack’s existential crisis upon leaving the Island as part of the Oceanic Six. He spirals into depression, alcoholism and even drug abuse, only to ignite a desperate yearning to return which marks the beginning of his transition into a man of faith. Off-Island, Jack’s rational life unravels – he grows a long beard, becomes suicidal and obsesses over the Island, as he is still haunted by his father and Locke’s posthumous plea to go back. Blaming himself for abandoning the survivors, Jack’s crisis peaks in a failed suicide attempt, where he realizes the Island’s pull is inescapable and he needs to return. Fox’s portrayal here is very harrowing and the first time he truly shines. He sheds off Jack’s composed exterior finally revealing the broken man than was always there, yearning for meaning and purpose in his life that, just like Locke, he found on the Island.

Jack: “Every Friday night I, I fly from LA to Tokyo or, Singapore, Sydney. And then I, I get off and I, have a drink, and then I fly home.” Kate: “Why?” Jack: “Because I want it to crash, Kate. I don’t care about anybody else on board. Every little bump we hit or turbulence, I mean I, I actually close my eyes and I pray that I can get back.”

Kate: “And then you show up here with an obituary for Jeremy Bentham. When he came to me and I heard what he had to say, I knew he was crazy. But you…you believed him.” Jack: “Yes.”

Locke: “It’s not an island. It’s a place where miracles happen.”

Jack: “All the misery that we’ve been through… we’d just wipe it clean. Never happened.” Kate: “It was not all misery.” Jack: “Enough of it was.”

“I’ll do it… This is why I’m here. This is… this is what I’m supposed to do.“

As Jack returns to the Island, his science-fueled hero complex from the early seasons transitions into a faith-fueled messiah complex, evolving from merely fixing the world to saving it. This new-found zeal largely supplants his initial compassion and starts a rigid pursuit of his own supposed destiny, which devastatingly leads to the catastrophic incident that ironically initiates the chain of events causing the 815 crash. As a determined believer into the Island (though just like Locke, unable to fully correctly read Island’s signs), Jack orchestrates the detonation of a hydrogen bomb in 1977, convinced it will reset their lives and prevent the crash, but this faith-driven act fails spectacularly, hurling them back to the present and underscoring his error, temporarily destroying his faith. Fox navigates this shift with wonderfully zealous conviction that never veers into mania, but more becomes the subtle expression of that broken man who finally found something beautiful in his life, a purpose, making Jack’s faith empowering yet alienating – his expressions reflecting a purposeful determination, but also highlighting how his messianic drive prioritizes itself over the personal relationships.

“You know, when we were here before, I spent all of my time trying to fix things. But…did you ever think that maybe the island just wants to fix things itself? And maybe I was just…getting in the way?”

Jack: “This is our destiny.” Kate: “Do you know who you sound like? Because he was crazy, too, Jack.”

“I have no idea why. But I’m willing to bet you that if Jacob went to that trouble, that he brought me to this island for a reason, and it’s not blow up sitting here with you right now.“

The man of faith begins to lose his conviction in the aftermath of the incident, plunging him into doubt, but he eventually profoundly regains it in Jacob’s lighthouse – fully transitioning into the unlikely messiah that the Island and Jacob needed, while grappling with the tragedy of realizing Locke was right all along. His realization of being special and important and destined to be something he denied himself for so long is incredibly bittersweet, as especially Locke’s demise and Jack’s final meeting with him amplifies Jack’s regret. Fox’s subtle acting shines here, conveying a very quiet sense of epiphany and even subtler sorrow as his usual intensity transitions into a contemplative restraint.

Christian: “Are you sure I’m the one who doesn’t believe in you, Jack?”

“But nothing… nothing in my life has ever felt so right. And… I just need you to believe that.”

Jack’s journey of self-discovery culminates in his willing acceptance of the Island’s protectorship from Jacob, in his final stand against the Man in Black and in his tragic yet beautiful ultimate sacrifice to save others and the Island. Volunteering for the role, Jack undergoes a ritual to become the protector, gaining an intuitive connection with the Island, then battles the Man in Black in a knife fight, killing him with Kate’s aid before descending into the Heart of the Island to restore its light, ensuring the world’s survival at the cost of own his life. As he lays to die in the bamboo grove with Vincent by his side, Jack finally finds peace and happines, his arc completing a full circle from the crash site to his closure. In his final heroic moments, Fox embodies this heroism with gravitas, with physical exhaustion and a serene acceptance that craft the perfect and profound catharsis.

“I’d make a terrible dad.“

In the flash-sideways, Jack remains a surgeon, but embodies a man of faith in his skills rather than an absolute man of science. He is tasked with experiencing fatherhood for himself through his son David (a purgatory construct) while helping Locke regain his faith in miracles, ultimately operating to restore his mobility. This alternate reality allows Jack to confront his paternal fears, bonding with David in ways he never could with Christian, and mirrors his Island growth by encouraging Locke’s belief, leading to a successful surgery. Fox portrays this evolved Jack with gentle assurance beautifully realizing the balance between science and faith he couldn’t manage in his mortal life.

“You know when I was your [David] age, my father didn’t want to see me fail either. He used to say to me that…he said that I didn’t have what it takes. I spent my whole life carrying that around with me. I don’t ever want you to feel that way. I will always love you, no matter what you do.”

“Chrissy, why can’t I just bring him to a funeral home and make all the arrangements? Why can’t I really take my time with it? Because… because I need it to be done. I need it to be over. I just – I need to bury my father.”

Jack is the last to awaken in the flash-sideways, only remembering his life upon reuniting with Kate and encountering his father’s coffin, where a heartfelt reconciliation with Christian resolves his daddy issues – this scene stands as Fox’s finest, a beautifully acted moment of catharsis where Jack finally reconciles with his father – Fox delivers this with tearful sincerity, never going overboard with his profound release, but only ever authentically bonding with the person that marked his life the most in a pure and powerful manner. As he joins the others in the church to move on, his smile shows that Jack has found his fulfillment and can move on happy.

“If I can fix you, Mr. Locke, that’s all the peace I’ll need.”

Jack Shephard’s symbolic path parallels that of Jesus, but is humanized by Fox and the writers as a cautionary tale of pretentious rationalism, where initial denial of the divine leads to suffering, but also to an ultimate redemption through faith and sacrifice. As Jack is leads his flock through trials and tribulations he confronts self-doubt, zealots and a devilish adversary, then sacrifices himself to save humanity and experiences a form of resurrection in the afterlife, reuniting with his disciples and connecting with his estranged father. Fox grounds these messianic echoes in relatable humanity, portraying Jack’s early arrogance in science as a flaw that blinds him to greater truths, making Jack’s personal growth into a tall tale of a man of science’s painful transformation not into a, but into THE man of faith.

Sarah: “My hero, Jack.”

The Best Acting Moment: reunion with his father S06E18

Verdict: 5

Josh Holloway as James “Sawyer” Ford

“I’m a complex guy, sweetheart.”

Sawyer is a difficult character to realize because of his inherent contradictions – a man who embodies a villainous charm and a hidden heroism, requiring an actor to navigate layers of sarcasm, vulnerability, evil and growth without tipping too much into any of these directions. Sawyer is introduced as a self-serving con artist, quick with a quip and even quicker to exploit others, yet beneath this facade lies a traumatized soul capable of profound loyalty and sacrifice. Holloway makes this role that could have been initially one-note masterfully balanced – using his Southern charm to make each of Sawyer’s aspects feel rounded, by his comedy or by his drama. You can see that the difficulty lies in sustaining audience investment through Sawyer’s abrasiveness while subtly revealing his humanity, a task Holloway accomplishes pretty masterfully.

Kate: “I don’t buy it.” Sawyer: “Buy what?” Kate: “The act. You try too hard, Sawyer. I ask you to help a woman who can’t breathe, and you want me to kiss you? Nobody’s that disgusting.”

Sawyer’s beginnings on the Island paint him as a self-proclaimed bad man – a jaded con artist who hoards supplies, trades insults and manipulates survivors for his personal gain. Yet more often than not his actions often contradict this image, revealing glimpses of decency that hint at his more complex moral core. In the flashbacks we see he adopted the alias “Sawyer” from the man who ruined his life, perpetuating a cycle of cons that encompassed his life through witnessing his father’s murder-suicide after being swindled:

“It was his name. He was a confidence man. Romanced my momma to get to the money, wiped them out clean, left a mess behind. So I wrote that letter. I wrote it knowing one day I’d find him. But that ain’t the sad part. When I was 19, I needed 6 grand to pay these guys off I was in trouble with. So I found a pretty lady with a dumb husband who had some money. And I got them to give it to me. How’s that for a tragedy? I became the man I was hunting. Became Sawyer. Don’t you feel sorry for me.”

However, moments of Sawyer’s reluctant help to the survivors undercut his villainous posturing, suggesting a man using bravado as armor against his vulnerable childhood trauma. Holloway captures this tension with swaggering confidence laced with subtle hints at something more in his quieter scenes – this early part of the performance is especially fantastic in Sawyer’s self-loathing in his confession where he admits to becoming the very monster he hunts, blending roguishness with ultimate underlying goodness.

Policeman: “James Ford. Assault, wire fraud, identity theft, bank fraud, telemarketing fraud… You’re a blight, a stain, scavenger. You’re a conman preying on the weak and needy. Tell me something, James, how do you live with yourself?” Sawyer: “I do just fine.” Policeman: “Do you?”

Holloway’s incredible comedic skills shine through the timing and delivery of Sawyer’s razor-sharp wit, providing levity amid the Island’s horrors and making the character a standout source of humor. Sawyer’s arsenal of nicknames serves as both a defense mechanism and a great comic relief, delivered with Holloway’s impeccable drawling sarcasm that often steals scenes. Holloway’s indestructable charm helps Saywer’s comedic prowess to not only endear Sawyer further to audiences, but also humanizes him, balancing the character’s darker edges with an infectious energy that elevates Holloway’s dynamics with the rest of the ensemble.

Jack: “...all I’m gonna get is a snappy one-liner, and, if I’m lucky, a brand-new nickname.”

Libby: “How’d you get shot, anyway?” Sawyer: “With a gun.” Michael: “He got shot when they took my kid.”

The slow acceptance of the conman begins as Sawyer grapples with his self-perception, gradually realizing he isn’t inherently bad and can achieve greater worth by releasing his trauma. The transformation is marked by incremental acts of heroism and vulnerability. Sawyer’s defenses crack particularly with Kate, whose shared outsider status prompts him to confront his past. Holloway portrays his self-reflective evolution not fast, but also not gradually, but combining Sawyer’s moments of good or of vulnerability between his usual “bad” persona, until these moments start to dominate his personality and even he himself isn’t aware of the shift. This acceptance peaks in moments of quiet introspection, where Holloway’s extremely expressive eyes convey his internal battles, illustrating Sawyer’s journey from self-sabotage to self-worth, transcending his bad guy persona through courage in his empathy.

“I ain’t doing nothing until I know my friends are OK.”

Locke: “You [Anthony Cooper] make people think that you’re their family. And then you leave their life in ruins. And I’m not gonna let you do it again.”

With “help” from Locke, Sawyer encounters Anthony Cooper (Locke’s father) trapped on the Island. This is the original “Sawyer” who conned his parents, leading to Sawyer’s consequent life of cons and misery. Holloway delivers a powerhouse performance in his slow realization of who this man actually is, his voice trembling with the suppressed rage as he wants him to finally read his childhood letter and the final powerful release of hate-fueled energy as Sawyer strangles Cooper, fulfilling a lifelong vendetta. This direct grappling with trauma forces Sawyer to see the cycle of vengeance he’s perpetuated, with Holloway’s raw intensity in the sequence capturing the hateful catharsis, but also some self-reflection, marking a turning point that puts Sawyer toward genuine change.

“I used to lie for a living.“

The killing of Cooper sort of concludes Sawyer’s hero’s journey, as it is soon followed by his selfless sacrifice to ensure the helicopter escape off the Island. Sawyer leaps from the chopper to lighten its load, saving Kate and the others at the cost of stranding himself again on the Island. The act is even more poignant as he whispers about his daughter to Kate, revealing his evolved priorities. Holloway infuses this moment with earned heroic resolve as the conman becomes a true hero through altruism – and some human fear.

Ben: “James. Look at yourself. Yes, on this Island you’re brave, daring, handsome, you’re someone, but if you left with them, back in the real-world a low-life scam artist like you could never compete with a first class surgeon.”

“I had a thing for a girl once. And I had a shot at her, but I didn’t take it. For a little while, I’d lay in bed every night, wondering if it was a mistake. Wondering if… I’d ever stop thinking about her. And now I can barely remember what she looks like. I mean, her face… it’s.. She’s just gone, and she ain’t never coming back. So… Is three years long enough to get over someone? Absolutely.“

Finally building a stable life with Juliet in the Dharma Initiative during the 1970s time shift, Sawyer adopts the alias James LaFleur, spiritually thriving as the head of security in a domestic bliss that contrasts the former Island chaos. For three years, he and Juliet form a loving partnership, with Sawyer shedding his sarcasm almost entirely for sincerity and love, managing Dharma operations with competence and care. Holloway portrays this matured Sawyer with quiet contentment with his present existence, at peace with his past – the performance highlights the character’s capacity for normalcy and love, making this era a bittersweet highlight of stability before the impending tragedy.

“You just don’t get it, Kate. We were happy in Dharmaville ’til y’all showed up.”

“It’s not your fault she’s dead… It’s mine. She was sittin’ right there, right where you are now, tryin’ to leave this place – and I convinced her to stay. I made her stay on this island because I didn’t want to be alone. You understand that right? … But, uh… But I think some of us are meant to be alone.”

The tragic destruction of this life occurs when the Oceanic Six return and Jack plans to destroy the Island with the hydrogen bomb. The incident culminates in Juliet’s death at the Swan site explosion, hurling Sawyer back to the present where he must process this final heartbreak – a new package of pain and suffering. Blaming Jack for his tragedy, Sawyer’s grief manifests in rage, but he quickly channels it into heroism as he sees the Man in Black for the conman he is and decides to help yet again and later escapes on the Ajira plane.

“I… got to a point in my life where I was either going to become a criminal or a cop. So I chose cop.”

In the flash-sideways, James also obsesses over Cooper, but now on the right side of the law as Detective Ford, embodying a truly good man who channels his childhood vendetta into a quest for justice in the world. This alternate self, free from the conman’s burden, investigates crimes with integrity and charm, reflecting his Island growth in this lawful framework. Holloway plays this version with authoritative poise, highlighting Sawyer’s inherent goodness without the trauma’s shadow – never sacrificing his charisma in the process.

Kate: “You [Detective Ford] don’t seem like a cop to me.”

Detective Ford awakens upon meeting Juliet at the hospital vending machine, their touch sparking their memories in one of the finale’s many beautiful reunions, reaffirming their soulmate bond in the afterlife. The tender moment nicely echoes their Dharma days and Holloway’s expressions nicely capture the profound closure for this complex character.

Sawyer’s beautiful journey illustrates a bad man who slowly embraces his good side through heart and heartbreak, forming a redemption from trauma via love, sacrifice and self-forgiveness. From con artist to hero, Holloway’s performance renders this arc incredibly compelling as he blends wit, pain, romance and growth into a testament to the potential of humanity even in the worst of us.

Michael: “Since the day you [Sawyer] told me you wanted on this raft, I couldn’t figure it out. Why does a guy who only cares about himself want to risk his life to save everyone else? The way I see it, there’s only two choices – you’re either a hero or you want to die.”

The Best Acting Moment: Sawyer meets Sawyer S03E19

Verdict: 5

John Terry as Dr. Christian Shephard and the Man in Black 4.5

Naveen Andrews as Sayid Hassan Jarrah 4.5

Elizabeth Mitchell as Juliet Burke 4.5

Daniel Dae Kim as Jin-Soo Kwon 4.5

Yunjin Kim as Sun-Hwa Kwon 4.5

Jorge Garcia as Hugo “Hurley” Reyes 4.5

Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje as Mr. Eko 4

Dominic Monagham as Charlie Hieronymus Pace 4

Nestor Carbonell as Richard Franklin Alpert 4

Titus Welliver as the Man in Black 4

Evangeline Lily as Katherine Anne Austin 4

Ken Leung as Miles Straume 4

Jeff Fahey as Frank Lapidus 4

Jeremy Davies as Daniel Faraday 4

Mark Pellegrino as Jacob 4

Kevin Tighe as Anthony Cooper 3.5

Fionnula Flanagan as Eloise Hawking 3.5

Emilie de Ravin as Claire Littleton 3.5

Harold Perrineau as Michael Dawson 3.5

William Mapother as Ethan Rom 3.5

François Chau as Pierre Chang 3.5

L. Scott Caldwell as Rose Nadler 3.5

Cynthia Watros as Elizabeth “Libby” Smith 3.5

Alan Dale as Charles Widmore 3

Mira Furlan as Danielle Rousseau 3

Sam Anderson as Bernard Nadler 3

Sonya Walger as Penelope “Penny” Widmore 3

Lance Reddick as Matthew Abaddon 3

Rebecca Mader as Charlotte Lewis 3

Ian Somerhalder as Boone Carlyle 2.5

Tania Raymonde as Alexandra Rousseau 2.5

Michelle Rodriguez as Ana Lucia Cortez 2.5

Zuleikha Robinson as Ilana Verdansky 2.5

Kiele Sanchez as Nikki Fernandez 2.5

Malcolm David Kelley as Walter “Walt” Lloyd 2

Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford 2

Kevin Durand as Martin Keamy 1.5

Rodrigo Santoro as Paulo 1.5

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Δdocument.getElementById( "ak_js_1" ).setAttribute( "value", ( new Date() ).getTime() );

.png)

Comments