Ephemeral Bliss: Between Hamilton’s Beaches and Shelley’s Shores

- goldenstateservicesj

- Sep 14, 2025

- 7 min read

“We two will rise, and sit, and walk together,Under the roof of blue Ionian weather…Or linger, where the pebble-paven shore,Under the quick, faint kisses of the sea,Trembles and sparkles as with ecstasy—Possessing and possess’d by all that isWithin that calm circumference of bliss, And by each other, till to love and liveBe one…”

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, Epipsychidion)

David Hamilton, Girls on the Beach, c. 1970s

The beach has long existed as one of art and literature’s most charged landscapes. The beach in this artistic, poetic sense is not simply a geographical location but a symbolic threshold: the mutable place where land meets sea, solidity dissolves into fluidity, and the horizon invites both liberation and reflection. In the photographs of David Hamilton, especially his pictures of young women on Mediterranean beaches, this liminality becomes a metaphor for another borderland; the fragile, dreamlike passage between girlhood and womanhood. David Hamilton’s photographs, marked by his distinctive soft-focus haze and sun-saturated tones, are less documentary than atmospheric. They seek not to record life as it is but to capture a mood, an aura, and fleeting states of being. On the beach, this mood becomes especially poignant. Hamilton’s girls are seen collecting pebbles on the beach, reclining on towels, strollomg barefoot on warm sand, or gazing outward to the glittering expanse of sea. What emerges is less the portrait of an individual than a poetic meditation on youth, freedom, and the delicate balance between innocence and awakening sensuality.

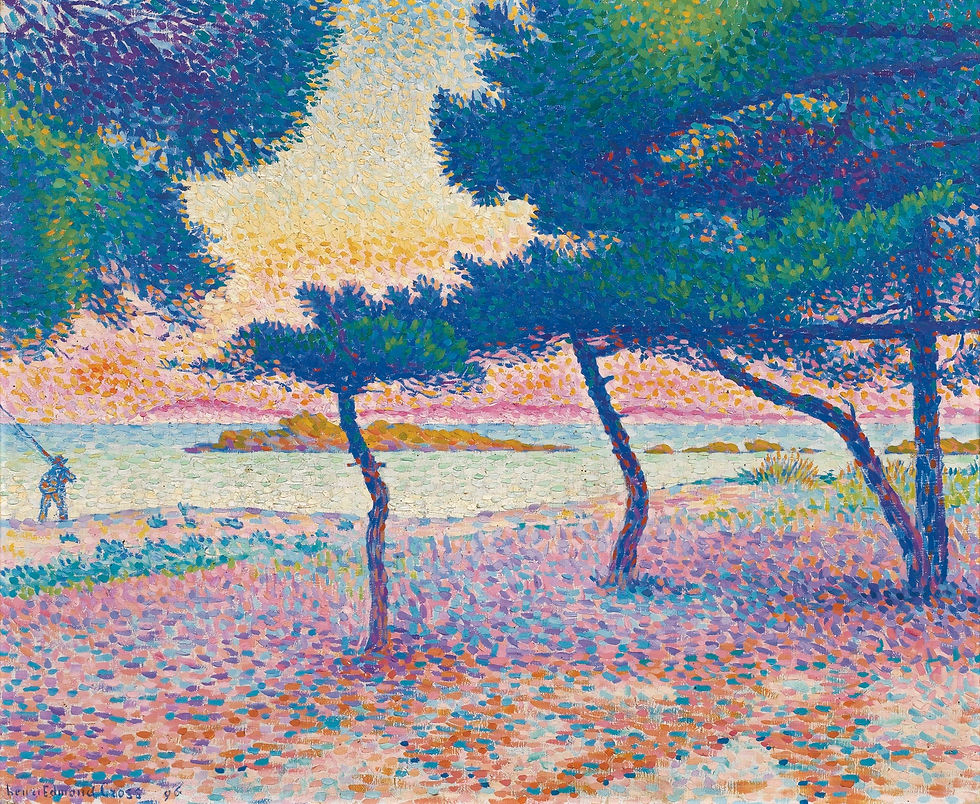

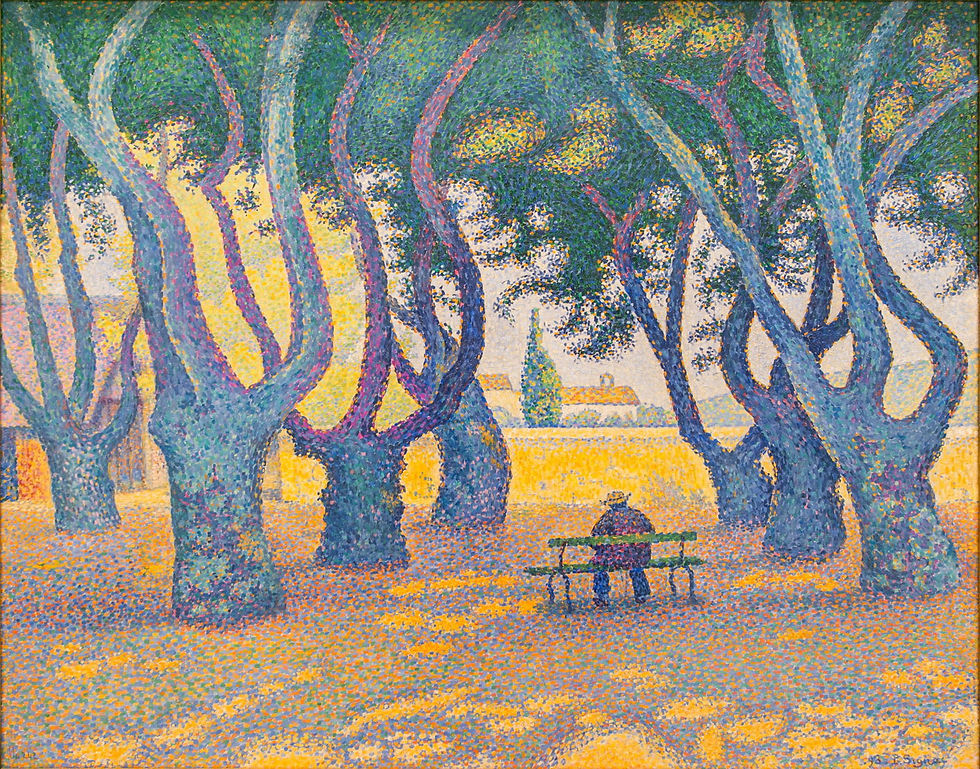

We cannot approach Hamilton without acknowledging his technical hallmark: the softened lens, the diffusion of outlines, the gauzy veiling of forms in light. On the beach, this technique acquires a particular resonance. Sunlight itself seems to dissolve the body into radiance. Rather than being defined by shadow and contrast, Hamilton’s subjects are enveloped in a golden light, their edges blurring with the sand, the sea, and atmosphere. This aesthetic echoes some beautiful Neo-Impressionist Pointilism paintings, where artists such as Paul Signac, Seurat or Henri-Edmond Cross sought to capture light as a living, mutable presence rather than as static illumination. In Hamilton’s photographs, the Mediterranean sun becomes not just backdrop but protagonist. It softens, caresses, and transfigures, turning the beach into a realm of perpetual summer. Youth, under such light, appears timeless, suspended outside ordinary chronology. The softness also has a psychological effect. Rather than presenting the subjects as sharply individualised, it renders them archetypal. They embody the universal mood of adolescence at the threshold, a fleeting stage that resists definition. Just as the contours of the body blur in Hamilton’s lens, so too do the boundaries of identity in youth, hovering between what has been and what is yet to come.

Paul Signac, Concarneau, Return of the Sloops, Op 222, 1891

David Hamilton, From the Book Les Demoiselles d’Hamilton, 1973

In David Hamilton’s photography, innocence meets sensuality. The beach is always a site of exposure. Clothing is shed, skin meets the natural elements, and the body is both revealed and naturalised. For Hamilton, this openness becomes a metaphor for the ambivalence of adolescence: the playful freedom of childhood overlapping with the first awareness of desire and self-presentation. The girls in his photographs often appear at ease, caught in gestures of repose or play, yet there lingers an unmistakable poise. They know, even if only intuitively, that they are being seen. The camera translates this subtle awareness into imagery that oscillates between innocence and sensuality. It is not eroticism in its explicit sense but rather an atmosphere of suggestion; the ‘not yet’ and ‘the almost’. Literature, particularly the Romantic and post-Romantic tradition, often sought to articulate precisely this threshold. One is reminded not only of Shelley’s verses in the already quoted poem ‘Epipsychidion’ but also these verses in his poem ‘Love’s Philosophy’:

“And the moonbeams kiss the sea— What is all this sweet work worth, If thou kiss not me?”

Here too, natural imagery becomes inseparable from desire. The kiss of the the sea and moon reflects the human yearning for intimacy. In Hamilton’s beach scenes, the sun’s caress on skin, the salt glitter on hair, and the gentle winds all participate in a similar metaphorical register. Nature itself becomes eroticised, not in the sense of overt sexuality but as a sensual continuum that mirrors the awakening body.

Henri-Edmond Cross, The Beach at Saint-Clair, 1896

In Hamilton’s imagery there is alwaya a sense of Mediterranean timelessness, a continuity with myth. The sea, the islands, the olive groves, they belong to the same geography that once nurtured Sappho’s songs and Shelley’s visions. It is this quality that draws us naturally toward Shelley’s poem “Epipsychidion”, that long hymn to a beloved spirit who embodies for him the fusion of innocence and passion, transcendence and earthly love. In one of the poem’s most luminous passages, Shelley writes of two lovers rising and walking together “under the roof of blue Ionian weather,” “lingering on the pebble-paven shore”, trembling with the “quick, faint kisses of the sea”. Hamilton’s girls are not Shelley’s lovers, but they seem to inhabit the same imagined landscape: a Mediterranean infused with light, where the body and the soul are not at odds but harmonise in beauty. Both Hamilton and Shelley are preoccupied with the threshold. Shelley’s poem continually moves between speech and silence, between thought and look, between earthly love and the idealised union of souls. Similarly, Hamilton’s photographs exist at the threshold between innocence and sensuality. His subjects are captured in gestures that are almost unselfconscious: a downward glance, a hand brushing away hair, the simple curve of a bare shoulder catching the sunlight. There is no theatricality, only the quiet radiance of youth where eros is not yet hardened into experience but felt as possibility, as the awakening of a self in relation to the world.

Paul Signac, Saint-Tropez, Plane Trees Op 242, 1893

David Hamilton, Vogue, April 1977

David Hamilton, Girl with the Shell, 1970s

The connection is most profound in their shared sense that love, beauty, and freedom are inseparable from nature. Shelley writes of lovers whose “breath shall intermix” and whose veins shall “beat together” as they merge with each other and the wider cosmos. Hamilton’s girls on the shore are immersed in precisely this unity: the sea breeze in their hair, the salt on their skin, the sun weaving shadows across their bodies. The photographs dissolve boundaries, between figures and the background, between childhood and adulthood, between innocence and eroticism, so that the viewer perceives a moment of pure, unrepeatable harmony. In this way, both Hamilton and Shelley offer us visions of fleeting perfection, an ephemereal bliss. They remind us that beauty is not eternal in the material sense, but eternal in the intensity with which it is experienced in the present. A memory of Beauty does NOT fade. The girl on Hamilton’s beach, caught just as a wave curls at her feet, is as transient as the seafoam; yet she is also as enduring as the archetype she evokes: youth on the verge of self-discovery.

Thus, when looking at Hamilton’s Mediterranean girls through the lens of Epipsychidion, one realizes that both artist and poet are seeking to articulate the same truth: that innocence and sensuality are not opposites but phases of the same unfolding, and that human love, fragile as it is, can still open out toward the infinite. The beach, the sun, the sea; these are not backdrops but emblems of this passage. Hamilton’s blurred lens and Shelley’s lyrical cadence converge in the same mood: the tremulous ecstasy of becoming, the shimmering vision of youth poised between the earthly and the eternal bliss.

Henri-Edmond Cross, Sunset Over the Sea, 1896

David Hamilton’s photographs are deeply Mediterranean in atmosphere. Though he worked in various locations, his palette of sun, sand, and sea evokes the timeless idyll of southern Europe: whitewashed villages, azure horizons, olive groves, and the indolence of the eternal summer. This Mediterranean backdrop recalls centuries of Western artistic fascination with the South as a locus of beauty, leisure, and sensuality; all the way from the Arcadian landscapes of classical poetry to the sun-drenched canvases of Matisse and Renoir. On the beach, the Mediterranean becomes not just a setting but a mood. The glittering horizon suggests infinity, the waves rhythmically whisper of time’s passage, and the open expanse mirrors the openness of youth. For Hamilton, the sea is both the backdrop and metaphor: its vastness corresponds to the limitless possibilities of becoming, its tides to the ebb and flow of innocence and desire. The Mediterranean also functions as a mythic space. The beach is the place where Aphrodite rose from the seafoam, where sirens rested on rocks rising from the sea. Hamilton’s figures, reclining in sunlight or walking barefoot along the shore, seem to echo these ancient archetypes. They are not depicted as models but as timeless presences, embodiments of youth poised on the brink of transformation.

Georges Seurat, Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp, 1885

What gives Hamilton’s beach photographs their enduring mood is the tension between fragility and freedom. On one hand, the subjects radiate ease, they are carefree, barefoot, sunlit, and fully immersed in the pleasures of summer. On the other hand, the very softness of the photographs imbues them with melancholy. The viewer senses that this state of being, this moment of unselfconscious youth, is fleeting, already vanishing into memory. This is why the photographs often feel nostalgic even as they depict the present. They shimmer with the awareness of their own ephemerality. Just as the sun begins to dip toward the horizon, casting its golden haze, so too does youth lean toward its inevitable fading. In this sense, Hamilton captures not simply the beauty of adolescence but the poignancy of its brevity. To look at David Hamilton’s beach photography is to enter a dream of perpetual summer, where youth is bathed in golden light, where innocence and sensuality overlap, where freedom is touched by fragility. The Mediterranean sea and sky become mirrors for the inner landscape of adolescence, shimmering with beauty even as they signal its transience.

Henri-Edmond Cross, Golden Isles, 1891-92

David Hamilton

In this way, Hamilton’s photographs are less about the body than about atmosphere, less about portraiture than about mood. They remind us that adolescence, like summer, is always fleeting, always already dissolving into memory. The sunlit beaches of his imagery are at once real and symbolic: real in their Mediterranean details, symbolic in their evocation of thresholds crossed, of youth awakening to desire, of innocence poised on the edge of transformation. In the end, Hamilton’s vision is nostalgic even as it is immediate. His beaches shimmer with the recognition that what is most beautiful is also most fragile; that the freedom of youth, like the golden haze of late afternoon, can only be held in memory, never in permanence…

.png)

Comments